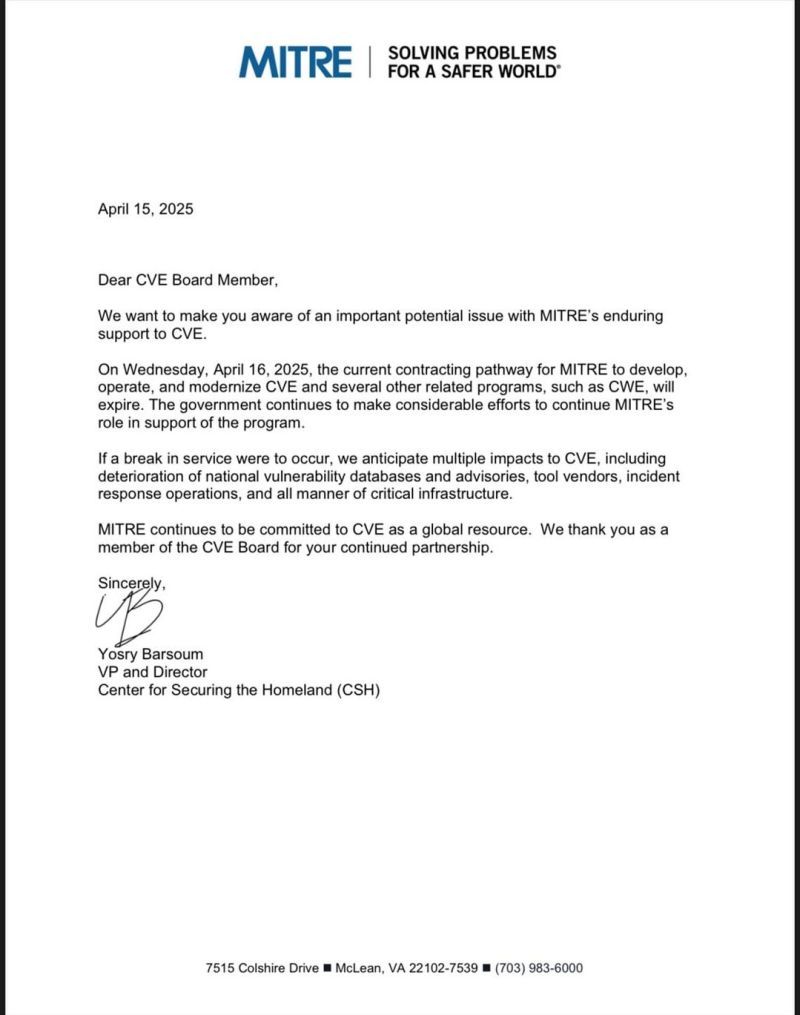

Update (April 16, 2024, 4pm GMT): CISA announced it’s extending MITRE’s Federal contract by 11 months, basically ‘saving’ the CVE Program at the 11th hour. But, ‘the wheels’ were already in motion, and concerns were raised whether a globally relied-upon resource like the CVE Program should be tied to a single government sponsor.

On April 15, 2025, the cybersecurity world was rattled by news that the CVE (Common Vulnerabilities and Exposures) program – the backbone of global vulnerability disclosure – may be entering uncertain territory. MITRE, the nonprofit that has operated the CVE system since its inception in 1999, announced that its contract with the U.S. government to fund and maintain the program has expired. While the CVE database is not “shutting down” in the immediate sense, the end of federal support introduces serious questions about the program’s continuity and long-term stability.

Why CVEs Matter

CVE identifiers are essential to modern cybersecurity. They provide a standardized naming convention for publicly disclosed software and hardware vulnerabilities, allowing vendors, security professionals, governments, and researchers to talk about the same issue with the same ID across tools and systems. Whether you’re patching a server, securing a medical device, or updating an enterprise application, CVE references underpin the risk management process.

When a vulnerability is discovered, security researchers or vendors typically request a CVE ID to ensure the issue is publicly recognized and tracked. From there, resources like NIST’s National Vulnerability Database (NVD) further analyze and enrich the record with severity scores (CVSS), attack vectors, and potential mitigations.

What’s Happening Now

MITRE’s announcement of the funding lapse places the entire CVE infrastructure at a crossroads. Without government support, the ability to issue new CVEs, manage assignments across hundreds of CNA (CVE Numbering Authorities) partners, and maintain the quality and accuracy of the database could be severely impacted. Also at risk is the Common Weakness Enumeration (CWE) project, another MITRE-maintained initiative that classifies root causes of vulnerabilities – a critical resource for secure development practices.

At the same time, the National Vulnerability Database, managed by NIST, is experiencing its own challenges. NIST publicly acknowledged in February 2024 that it was facing a significant backlog in enriching CVE records. A proposed consortium of government, industry, and academia is intended to help revive NVD’s capabilities, but it remains unclear how and when that group will be formed.

What’s at Stake

The potential disruption to the CVE program doesn’t just affect software vendors and IT departments. It threatens the foundation of coordinated vulnerability disclosure and incident response globally. Without timely and consistent CVE entries:

- Attackers gain the upper hand: Delayed disclosure or inconsistency in identifying vulnerabilities creates windows of opportunity for threat actors.

- Compliance becomes complicated: Regulatory frameworks like ISO 21434, NIS2, HIPAA, and the Cyber Resilience Act (CRA) all depend on standardized vulnerability tracking.

- Coordination suffers: CVEs provide the common language that connects CERTs, PSIRTs, open source maintainers, and commercial vendors. A breakdown here could lead to fragmented and slower responses.

Possible Outcomes

1. Government Reinstates Funding: The most optimistic outcome is that U.S. federal agencies step in to extend or renew funding for MITRE’s stewardship of the CVE program. Given the program’s international significance, this would likely come with additional oversight and commitments to modernization.

2. Public-Private Governance Model: Inspired by the proposed NVD consortium, the CVE program might evolve into a hybrid governance model, where major tech companies, government agencies, and nonprofits share responsibility. This approach could stabilize funding and diversify decision-making.

3. Alternative Vulnerability Databases Gain Prominence: If the official CVE system falters, industry might pivot to alternative databases like GitHub Security Advisories, OpenCVE, or vendor-specific portals. However, none of these offer the universal coverage or neutrality of CVE.

4. Fragmentation and Inconsistency: In a worst-case scenario, the global vulnerability disclosure ecosystem could fragment, with inconsistent tracking, duplicate entries, and reduced transparency. This could erode trust and increase risk across sectors.

What Security Teams Should Do Now

Security leaders should continue monitoring CVE activity and prepare contingency plans – engaging with CNA partners, subscribing to multiple vulnerability intelligence sources, and contributing to industry-wide initiatives may become necessary to ensure continuity.

While the CVE system isn’t gone yet, the warning signs are clear: this is a pivotal moment for anyone dealing with cybersecurity.